In the past few months, as normalisation talks have been proceeding between north and south Korea, with arrangements being made for south Korean citizens to be able to reunite with their families in the north, large numbers of north Koreans stranded in the south have been hoping that their plight will be taken up by the south Korean authorities so that they will be able to return home.

One such person is Mrs Kim Ryon Hui, who has been protesting against her detention in south Korea and demanding to be allowed to return home ever since she was tricked into going to south Korea in 2011.

Her story is that she had visited China for medical treatment, only to be faced with a large bill that she had never expected from a socialist country. She needed to earn money to pay it and was offered relatively well-paid work that she understood would be temporary in south Korea, so that she could pay her bill and return home all the sooner to her doctor husband and her young daughter.

“But when she arrived in the south she quickly realised it was a one-way ticket. Like all north Korean defectors, she was interrogated by agents from the National Intelligence Service and required to sign a statement disavowing any support for the north. She also automatically became a south Korean citizen, and it is illegal to visit the north without government approval.

“Kim planned to apply for a passport and return, but was rejected when the authorities discovered her destination was Pyongyang.” (‘Forever strangers’, the north Korean defectors who want to go back by Benjamin Haas, The Guardian, 26 April 2018)

She hated life in south Korea. She was appalled by the sight of homeless people in the streets, as nobody is homeless in the north where, if all else failed, fellow citizens would provide a home until the authorities were able to settle them in a home of their own.

Ms Kim told the Guardian: “Living here for seven years taught me what it really is like to live here as a north Korean defector. North Korean defectors are forever strangers in this country, classified as second-class citizens. I would never want my daughter to live this life.

“North Korean defectors are treated like cigarette ashes thrown away on the streets.”

And the Guardian also noted: “Half the north Koreans now living in the south say they have faced discrimination, including from employers, colleagues and even strangers on the street.”

Ms Kim has been surprised how uninformed south Koreans are about life in the north and now makes a point of explaining to everybody she meets how much more pleasant life is in the north as compared to the south.

Another north Korean who did defect in the hope of being able to raise money for medical treatment for his son that was not available in the north is Kwon Chol Nam. It was not long after arrival, however, that he began desperately to regret his decision, as he found he was discriminated against, and his employer failed to pay him his promised wages.

“To live a life, money is an important factor, but the most important thing is to be treated like a human being. In the north, no one treated me like that,” he said. “When I arrived [in south Korea] I was told I would be treated equally but that was bullshit.”

He too has done everything he could to persuade the authorities to allow him to return home, but he too, like Ms Kim, has only ended up spending months in prison for his pains.

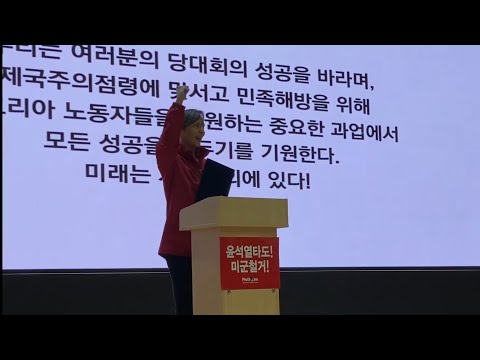

Both he and Ms Kim now devote all their energies to publicising their cause.